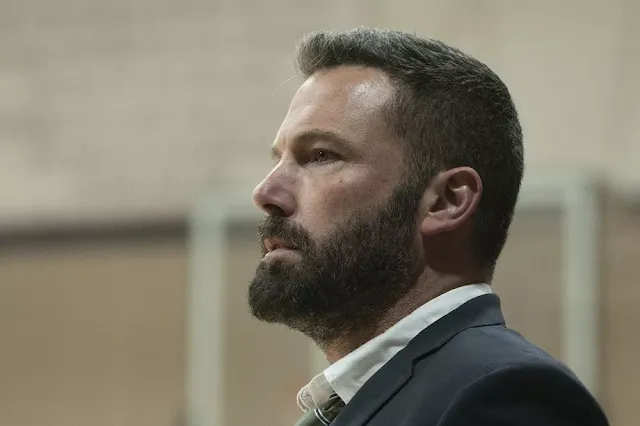

The Way Back stars a terrific Ben Affleck as a grieving alcoholic basketball coach

|

| The Way Back stars a terrific Ben Affleck as a grieving alcoholic basketball coach |

Ben Affleck’s offscreen life weaves into his excellent performance.

I like watching Ben Affleck perform. He has a bit of an old-school movie star quality about him, taking up space on screen, drawing your eye wherever he goes. He’s a big man, and when he emotes, you can feel the energy vibrating off of him. The quality of his movies has varied wildly over the past few years (and his last film, The Accountant, directed, like this film, by Gavin O’Connor, was actively bad), but he has that distinctive quality that marks out a movie star — no matter who he’s playing, you don’t forget you’re watching Ben Affleck perform.

But for years, the off-screen Affleck has overtaken the on-screen one, fodder for tabloid gossip (largely about his addictions and disintegrating marriage to Jennifer Garner) and “Sadfleck” memes that furnished a public narrative for private turmoil. The problem with being a star is that if people are thinking about you while you’re acting, they’re bringing all your baggage into watching your movie.

|

Ben Affleck’s offscreen life weaves into his excellent performance.

|

That’s why The Way Back seems like the most appropriate vehicle for Affleck now as he fights his way out of what seems like some serious darkness in his own life. (The tagline on the movie’s posters is, unsubtly, “One shot for a second chance.”) The movie works quite well on its own, understated and willing to embody genre tropes while quietly subverting them. But Affleck’s history brings the story — of a grieving alcoholic trying to come back from the brink — both emotional heft and a kind of trustworthiness.

The Way Back starts out as a sports movie, but it turns into something more

Affleck plays Jack Cunningham, a former high school basketball star with strong prospects and a full ride to play college hoops. Now he’s a middle-aged construction worker and a raging (but relatively high-functioning) alcoholic. He hides booze on the job, keeps a beer in the shower, pounds can after can when he gets home at night, and has mostly cut himself off from other people — except his buddies down at the bar, who end up having to walk him home more nights than not.

|

Ben Affleck’s offscreen life weaves into his excellent performance.

|

At the start of The Way Back, the reasons for his addiction seem to be somewhat obvious: He and his wife (Janina Gavankar) split a year and a half earlier, and it sent him spiraling. But The Way Back isn’t quite as simple as that, and as the story unspools, so does Jack’s full backstory. It’s rarely just one thing that drives a person to addiction; a lifelong pile-up of pain drives Jack.

But it takes a while for those details to leak out. Jack is closed off and unrevealing, and the movie tracks with his emotional state. Which is why, instead of diving straight into his trauma, The Way Back first sets itself up as a sports movie. Jack gets a call from the priest in charge of his former high school who asks him to step in as basketball coach for the flailing team after the previous coach’s health problems take him out of the job.

Why Jack came to mind isn’t entirely clear, nor is it obvious why anyone thought a former star player would necessarily be a great coach. But the team is desperate. Jack is equally desperate to refuse — for reasons that take a long time to become clear — but eventually he relents and agrees to take the job.

The team is ragtag and undisciplined, far from Jack’s glory days in the mid-90s, but in typical sports-movie fashion, he whips them into shape (with a lot of accompanying profanity, to the team chaplain’s horror), and they finally start winning.

At this point, it’s easy to imagine The Way Back slipping into the easy grooves of a sports film, crossed a little with the “magical teacher” genre, especially since Jack is white and most of the team is not. Team starts winning, coach learns as much from the kids as they learn from him, somebody gets a scholarship, Jack confronts his demons. We know this outline.

But The Way Back never gets too comfortable in one place, and every time it feels as though it might be slipping into cliche, it half-twists into something new. The Way Back is a movie about an addict who happens to coach high school basketball, and the latter never overtakes the former. (In a telling move, we watch the lead-up to the first game but skip the game entirely, just showing the final score. This is not, the film reminds us, a story about the healing power of sports.) Sometimes the accumulation of misery in Jack’s past starts to feel like too much, as if it’s contrived; then again, it’s all well within the range of the possible, and the build-up of tragedy reminds us that Jack’s addiction likely didn’t spring up out of nowhere; it’s a learned behavior with a long, long tail.

The Way Back is an adult drama about redemption but without any cliches

As with last year’s Waves, it’s remarkable to note how The Way Back most closely resembles the “redemption” narratives that are familiar in inspirational films — and particularly wildly successful Christian films — but steps away from those films’ easy answers. Too often the genre is averse to depicting just how dark and broken people can become. And certainly the level of alcoholism and salty language in The Way Back disqualifies it instantly for the Christian movie genre, despite the many prayers and a few religious discussions.

But The Way Back isn’t just a redemption story; it’s also marked by an uneasiness with the idea that there’s some simple path out of hell for Jack or anyone like him. Life doesn’t get easier for him, the pain doesn’t go away, and the things he wants fixed aren’t going to resolve themselves. But something has shifted inside of him. He’s stepped onto a road that is leading somewhere.

|

| The Way Back stars a terrific Ben Affleck as a grieving alcoholic basketball coach |

Meanwhile, as Jack is forced deeper into past hurts he’s tried to bury, Affleck’s performance gets more and more raw. He always seems to be on the verge of tears and explosion. At one key moment, when he’s been brought to a breaking point, you can sense the volcano inside that’s propelling him toward destruction. It is painful to watch.

This is familiar territory for director O’Connor, who despite flubbing The Accountant has proven himself capable, in movies like Warrior and Miracle, of craving both a compelling sports drama and exploring something interesting about how men are taught — and then have to relearn — how to deal with challenge and grief and relationships.

The Way Back feels more mature than those films, no doubt due partly to Affleck’s performance. It hearkens back to the kind of original mid-budget films that were rampant in Hollywood in the 1990s, serious dramas for adults that aren’t necessarily hunting for awards-season glory. Movies like this one are just looking for an audience with whom they’ll resonate.

And the seriousness of The Way Back — its unwillingness to take the easy road, and Affleck’s total commitment to letting his personal rawness inform performed pain — should ensure those audiences find what they’re looking for.

Director Gavin O’Connor has been something of the sports movie guru over the past two decades. The director of the Olympics hockey crowd-pleaser Miracle and the MMA drama Warrior now turns his camera towards high school basketball with the new film, The Way Back. Basketball is just the cinematic vessel, though, for telling a story about alcoholism and overcoming one’s personal demons—a subject that is very personal for the movie’s star, Ben Affleck.

Affleck plays Jack Cunningham, a former high school star who gave up the game after graduation, despite being offered a full ride to Kansas. Twenty years later, Cunningham is working construction, separated from his wife, and drinking himself into a stupor every evening. One morning he receives a call from his old school, inviting him to take over coaching duties of the basketball team following the previous coach’s sudden retirement. After a night of some seriously heavy drinking (how does one drink that much of any beverage in a single evening?) in which he tries to figure out how to decline the offer—first politely, then…not so politely—Jack wakes up and decides to give it a go.

The school’s basketball program has done nothing but lose since Jack’s playing days and there aren’t many players to work with, but he immediately sees some potential, especially in the team’s quiet point guard Devon Childress. Devon is the mirror in which Jack’s own troubles will be reflected. Whereas Jack can be loud and aggressive, Devon is quiet and passive. Whereas Jack’s father was overly invested in his basketball skills, Devon’s has never seen him play. Whereas Jack chose to quit basketball to spite his father, Devon dreams of a basketball career in spite of his father’s wariness.

There are really only two other players who have any kind of impact on the film. Marcus is the tallest player on the team who would rather rain threes from beyond the arc than play in the paint. He also has a lackadaisical attitude and shows up late to games, a habit that leads to Jack expelling him from the team. And Kenny Dawes is the team’s ladies man, always last on the bus because he is saying goodbye to his latest sweetheart. His penance for his dalliances is one of the movie’s best comedic moments.

There are some great moments on the court. Jack’s first big “motivational” speech to his team is an all-timer, but maybe not for the reason you might expect from an inspirational sports movie (it is certainly a major factor in the movie’s R rating). And there are some great, cheer-worthy in-game moments. Gavin O’Connor certainly knows how to film scenes of athletic action to make them exciting and impactful, and this movie’s on-court scenes are top notch. My only quarrel with the basketball storyline is the believability of a team that was consistently being blown out suddenly becoming invincible after just one win.

As good as this movie is on the court, though, it is the scenes off of it that carry the emotional weight. In fact, the climax of the basketball storyline comes before the third act of the movie even starts.

The movie can easily be seen as an exploration of personal demons for Affleck, who stepped onto the set of this movie about alcoholism basically straight from rehab. That personal connection comes through in the performance. You can almost see him carrying the emotional weight of the movie’s exploration of alcoholism on his back and he is well up to the task of shouldering the load. It is certainly the most openly emotional performance he has delivered in years; maybe ever. It is clear that he trusts the direction of O’Connor, whom the actor previously worked with in 2016’s The Accountant.

Actors playing alcoholics can often play it too broadly, but Affleck’s performance rarely goes to extremes. He is reserved and often portrays his character’s drunkenness with simple looks or gestures. There is one moment where he is confronted while simply sitting at a table and just the way he holds his eyelids—each at a different level—tells you everything you need to know about his character’s current condition.

Affleck has said that part of the reason for doing this movie is that he wanted to get back to “acting.” Not movie stardom, but acting. If this is the beginning of Ben Affleck acting, then he is off to a really good start. The actor/writer/director has made a habit out of rejuvenating his career and this performance could prove to be the start of another great chapter.

Comments

Post a Comment